Tuesday 23rd March 17:00-19:00 GMT

Book Symposium on Satire, Comedy and Mental Health by Dieter Declercq. With:

Heike Bartel (Associate Professor in German, Nottingham),

Daniel Flavin-Hall (Consultant & Professor of Psychiatry, Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minnesota),

Sheila Lintott (Professor of Philosophy, Bucknell)

Orla Vigsö (Professor of Media Studies, Gothenburg)

Please find the recording of each invited speaker and Dieter Declercq’s response below.

About the book – A sample chapter can be read here.

Satire, Comedy and Mental Health examines how satire helps to sustain good mental health in a troubled socio-political world. Through an interdisciplinary dialogue that combines approaches from the analytic philosophy of art, medical and health humanities, media studies, and psychology, the book demonstrates how satire enables us to negotiate a healthy balance between care for others and care of self.

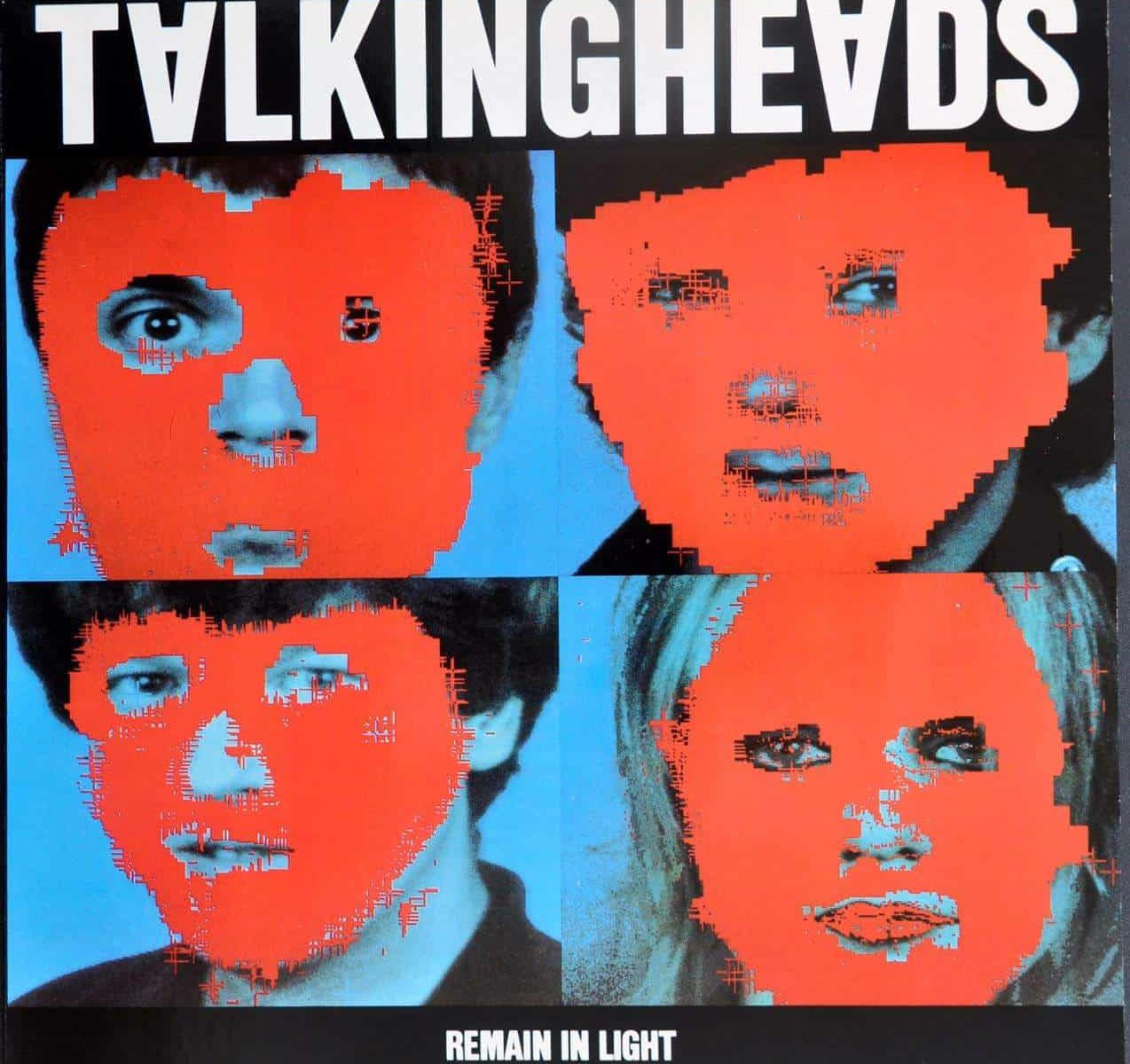

Building on a thorough philosophical explication and close analysis of satire in various forms – including novels, music, TV, film, cartoons, memes, stand-up comedy and protest artefacts – Declercq investigates how we can harness satirical entertainment to ease the limits of critique. In so doing, the book presents a compelling case that, while satire cannot hope to cure our sick world, it can certainly help us to cope with it.